Table of Contents

5-3 Geological History of Western Canada

Read Chapter 21 in Physical Geology.

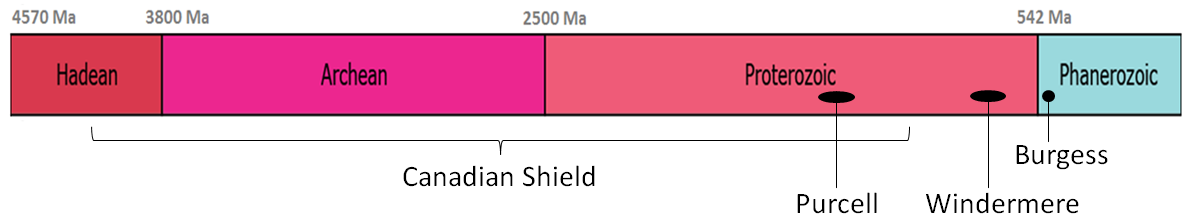

Chapter 21 provides an overview of the geological history of western Canada, but to provide context, we need to look at the ancient geological history of Canada as a whole, as summarized in Section 21.1. Most of central, eastern, and northern Canada are underlain by the world’s largest area of ancient rocks (the Canadian Shield), and Canada is home to the oldest rocks in the world (the Nuvvuagittuq greenstone, from the eastern shore of Hudson Bay, has been dated at 4.28 Ga, and the Acasta gneiss, from north of Yellowknife, has been dated at 4.05 Ga—see Figures 21.2.1 and 21.2.2). The Canadian Shield is the ancient continent of Laurentia.

While it’s not necessary to understand all of the rocks of the Canadian Shield to learn about the geology of western Canada, it doesn’t hurt to know something about them. Completing Exercise 21.1 will help you to gain a very high-level view of the geology of Canada.

The western part of the exposed Canadian Shield is made up of a number of different provinces that formed at different times and combined together due to a series of ancient continental collisions (Figure 21.2.1). All of the resulting mountain ranges have long since been eroded away, and these areas are now dominated by granitic and metamorphic rocks.

Some small areas of very old rocks in British Columbia—dated around 2 Ga (Figure 21.2.3)—may be part of the Canadian Shield, but by around 1400 Ma, new sediments were being deposited along this edge of Laurentia to form the Purcell Supergroup rocks that make up a large part of the southwestern Rocky Mountains and continue well into the United States. Considerably later (at around 700 Ma), the sediments of the Proterozoic-aged Windermere Group started to accumulate further to the north, and for the next few hundred million years—well into the Phanerozoic—sedimentation continued along this continental shelf, forming most of the sedimentary rocks that were later pushed up to become the Rocky Mountains.

Amongst the early Phanerozoic rocks of British Columbia is the Cambrian-aged Stephen Formation that includes the famous Burgess Shale Member, which is host to spectacular fossils that have changed and continue to change our perceptions of the evolution of early animals and plants (Figure 21.3.1 and Figure 5-7).

With respect to the geological time scale, Figure 5-8 illustrates some of the events that were significant to the early stages of the formation of western Canada.

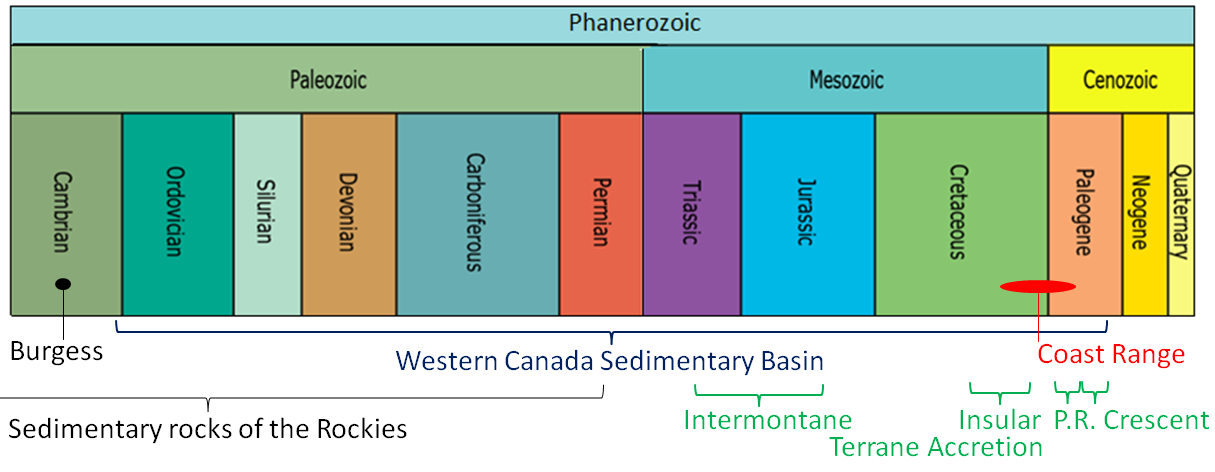

Accumulation of sediments along the Pacific coast of North America continued through most of the Paleozoic, during which time much of the west-central region of the continent also was under water. The Western Canada Sedimentary Basin persisted from the Ordovician through to the Paleogene (Figures 21.4.10 and 21.4.11 and Figure 5-9), accumulating both marine and terrestrial sediments ranging from deep-water mudstone to limestone, evaporite, and fluvial sandstone. Some of the important features of these rocks include thick and extensive potash deposits, various types of fossil fuels, and of course dinosaurs (Figures 21.4.12 and 21.4.13).

Meanwhile, after hundreds of millions of years, as a passive margin (meaning no plate-margin tectonic processes), the Pacific (a.k.a. Panthalassic) coast of North America transformed into a subduction margin during the Carboniferous era (Figure 21.3.3). As oceanic crust started subducting beneath the North America plate, small continents and islands that originally had formed far out in the Pacific gradually moved towards the coast. These blocks of continental crust, now part of North America, are known as terranes.

The first of the exotic blocks to reach North America, known as the Intermontane Superterrane, arrived here during the Triassic and Jurassic eras (Figure 5-9). These exotic blocks are composed of a number of smaller terranes and now underlie a significant part of central British Columbia, the Yukon, and Alaska (Figures 21.4.1 and 21.4.2). These terranes, which originally formed in the Pacific as groups of islands like those of Japan or Indonesia, are dominated by Paleozoic and Mesozoic volcanic and sedimentary rocks. As the Intermontane terranes converged with the western edge of North America, they slowly pushed the existing Proterozoic and Paleozoic sedimentary rocks to the east—by tens to hundreds of kilometres—creating the Rocky Mountains (Figures 21.4.3 to 21.4.7).

The second set of exotic terranes (the Insular Superterrane) arrived on the coast of North America during the Cretaceous. These rocks now make up Vancouver Island, Haida Gwaii, and much of the Alaska Panhandle, and their convergence helped to push the Rocky Mountain sedimentary rocks even further east, creating some unusual situations where old marine rocks originally deposited offshore now lie on top of younger rocks originally deposited within the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, as illustrated in Figures 21.4.6 and 21.4.7.

Completing Exercise 21.3 (in Section 21.3) will help you gain an understanding of the composition and age of the Wrangellia Terrane rocks (part of the Insular Superterrane) of Vancouver Island.

The subduction associated with the accretion of the Insular Superterrane produced a massive amount of volcanism along this part of the Pacific coast, and the associated magma bodies (granitic stocks and batholiths) cooled within the crust to form one of the most extensive belts of intrusive igneous rock on Earth. The Coast Plutonic Complex (Figures 21.4.8 and 21.4.9) extends north from Vancouver well into the Alaska Panhandle, and is the backbone of the Coast Range, which includes the tallest mountains in British Columbia, the Yukon, Alaska, Canada, and in fact all of North America (Figure 5-10).

During the Mesozoic, sediments continued to accumulate in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, while small terranes were being accreted to the west coast (Figures 21.4.10 and 21.4.11).

Exercise 21.4 is intended to help you understand the type of setting in which some of the Cretaceous sediments of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin were deposited, including those rich in dinosaur fossils.

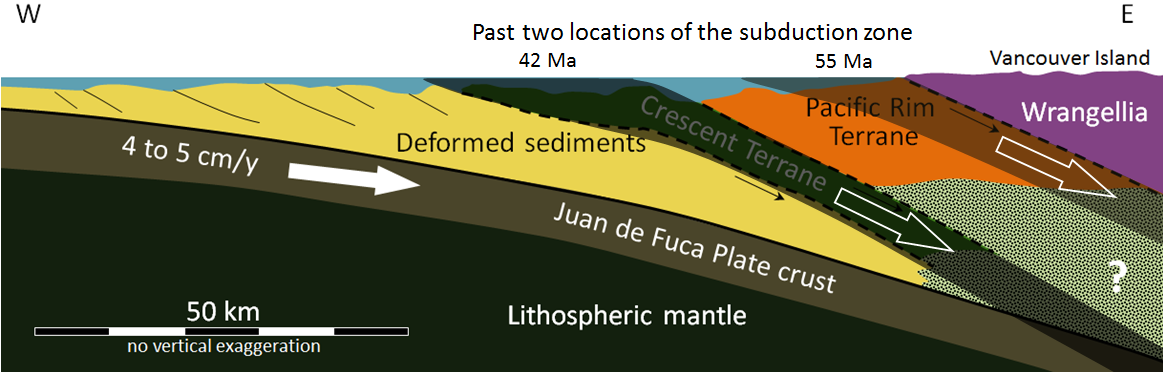

As described in Section 21.5, two additional terranes were accreted to the west coast during the Cenozoic. The Pacific Rim and Crescent Terranes make up the western part of Vancouver Island, and their accretion is responsible for the folding and uplift of Cretaceous Nanaimo Group rocks (Figures 21.5.1 to 21.5.3). As shown in Figure 5-11, the successive addition of exotic terranes has caused the shifting of the location of subduction along the continental margin. After the accretion of the Pacific Rim Terrane the subduction zone shifted about 40 km west, and after the accretion of the Crescent Terrane it shifted about 75 km further west, to where it lies today. Of course, this also implies that in the Paleozoic and Mesozoic, when the Intermontane and Insular Superterranes arrived on our coast, the subduction zone was well to the east of the current coastline, somewhere in what is now central British Columbia, and that this zone shifted west later at least once during the Mesozoic.

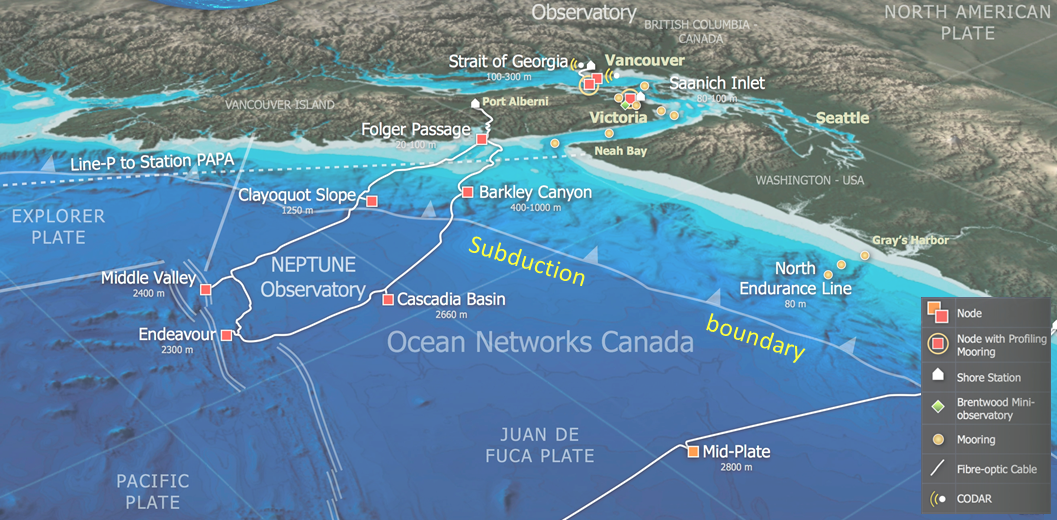

The modern-day plate tectonic situation along the western coast of North America is shown in Figure 21.5.4. The Juan de Fuca and Pacific Plates are forming along the spreading ridge. The Pacific Plate is moving to the northwest, sliding beside the North America Plate along the Queen Charlotte Fault (a transform fault) and subducting beneath the North America Plate south of Alaska. The Juan de Fuca Plate (and the Gorda and Explorer sub-plates) are subducting beneath the North America Plate beneath British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northernmost California. Composite volcanoes have formed inland from both of these subduction zones.

Exercise: For an animated overview of the geological history of Canada, please view the following.

Please answer the review questions at the end of Chapter 21.

This completes the notes for Unit 5.

If you haven’t already done so, now is the time to start working on Assignment 5 (go to the “Assignments Overview” area of your course). You should find most of what you need to complete the assignment within these course notes and Chapters 17, 19, and 21 of your textbook, but you also might need to refer to other sources of information.