Table of Contents

1-1 Introduction

Read Chapter 1 in Physical Geology.

Chapter 1 in Physical Geology provides an introduction to the science of geology, which is the systematic study of our Earth. As noted, geology involves a synthesis of knowledge from biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, and astronomy, so geologists must have a wide base of understanding. Geologists also must consider an additional factor—the vast amounts of geological time. The significance of this factor cannot be overstated.

As described in Section 1.1 in your textbook, geologists use scientific methods to study the Earth. The key attribute of a scientific enquiry is that it is based on formulating a hypothesis, making predictions that are consistent with this hypothesis, and then gathering data to test these predictions. If the hypothesis and the predictions are well thought out, if the data are carefully collected, and if the results support the predictions, we can say that the hypothesis is reasonable. However, all of these steps together don’t actually prove that a hypothesis is correct, since that would take many similar studies done under different conditions, which all corroborate the initial hypothesis. Two extremely important considerations for doing any kind of enquiry are to avoid jumping to conclusions without carefully assessing the available information, and to remain strongly skeptical about all results—your own and those of others.

Section 1.2 in your textbook includes a list of reasons why it’s important to study and understand the Earth, which are illustrated by the fatal 2005 slope failure in North Vancouver. Another example of the imperative to understand the Earth is related to climate change.

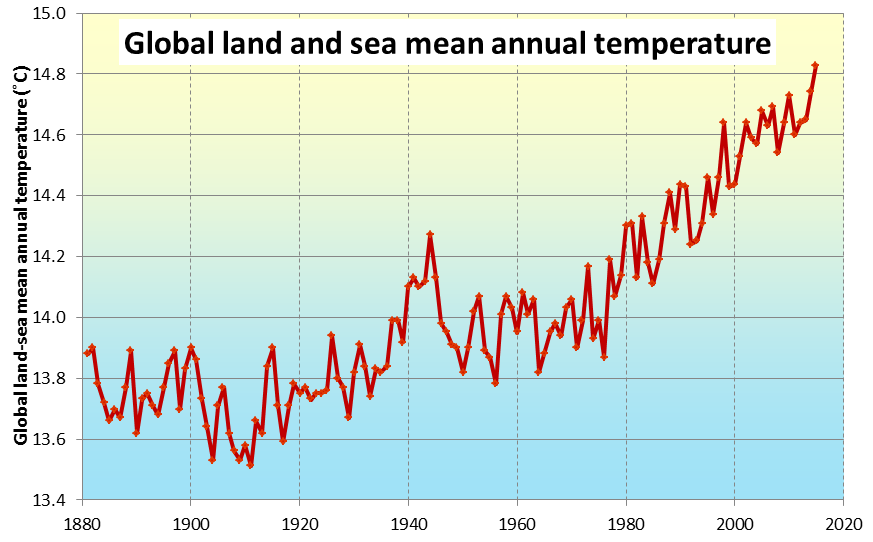

We know the climate is changing because we can see and feel the effects, which temperature records support (Figure 1-1). However, to really understand climate change, we need to know how this change compares with natural changes happening now and those that have occurred in the past, and we also need to know about a wide range of both natural and anthropogenic (human caused) factors that can cause the climate to change. Understanding these changes requires careful study of many different types of geological records, plus a strong knowledge of the chemical, physical, biological, and astronomical factors that affect our climate. We’ll look at these factors more closely in Unit 5.

Section 1.3 in your textbook includes a very brief discussion of the type of things that geologists do. If you think you might be interested in a career in geology, you’ll probably want to do a lot of reading about the various options for geologists and the opportunities for geological work where you live.

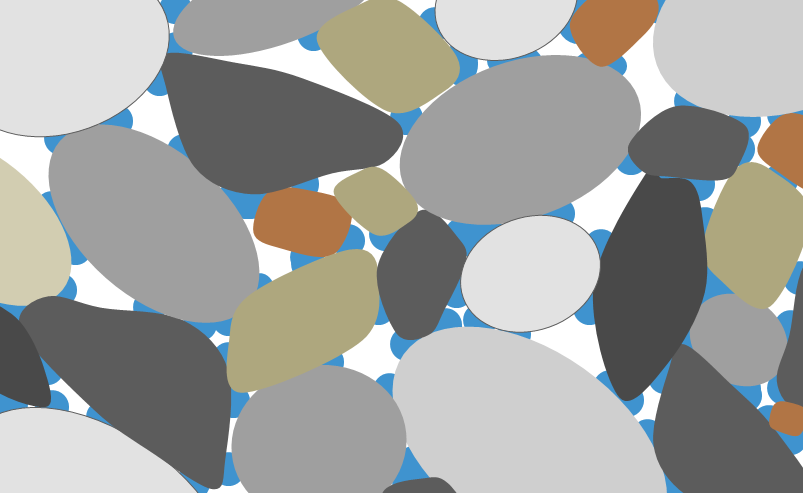

Section 1.4 in your textbook is an introduction to the concepts of minerals and rocks. Some of the emphasis is on the difference between minerals and rocks, which is important because we’ll be talking about both at some length during this course. You’ll need to work hard at keeping minerals and rocks separate in your mind, so that when asked, for example, to name a type of rock that might form in a certain setting, you don’t respond with the name of a mineral!

We’ll be looking much more closely at minerals and igneous rocks later in this unit.

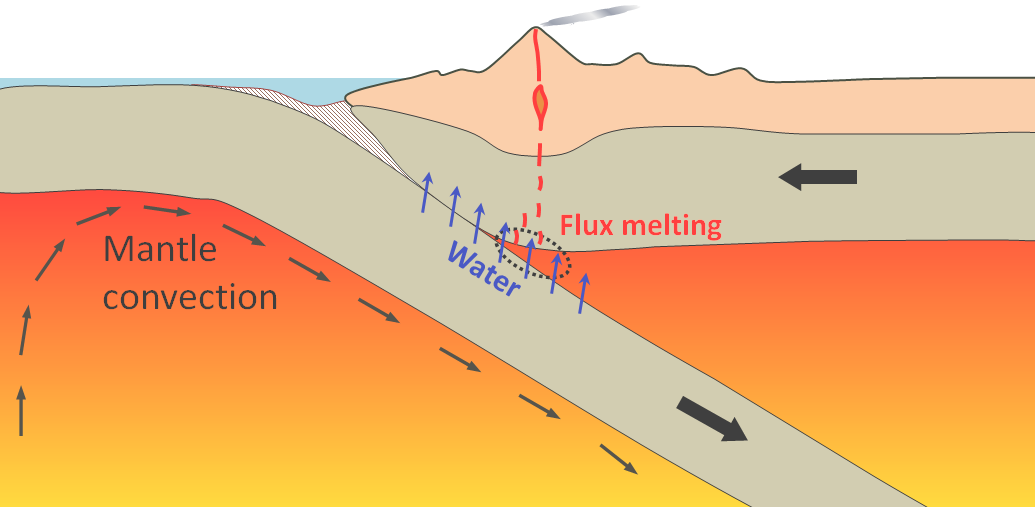

Section 1.5 in your textbook includes an introduction to plate tectonics. It’s important to read this part carefully because we’ll be referring to plate tectonics at just about every turn. Understanding the nature of the Earth’s interior is critical to understanding the plate tectonic processes, so look closely at Figure 1.5.1. We will be studying plate tectonics in much greater detail in Unit 3, but it wouldn’t hurt to have a quick read through Chapter 10 now before going any further.

Physical Geology has numerous built-in exercises to help you engage with concepts, rather than just reading about them. You will be specifically instructed to do some of these exercises within these course units, and now is the time to do Exercise 1.2.

For registered students: Exercise 1.1 involves going out and finding a piece of granitic rock. In fact, you’re asked to do just that for one of the exercises in Assignment 1, so you should probably go and have a look at the assignment soon. Some of the exercises require you to answer one or more questions; answers to the assigned exercises can be found at the end of your course textbook.

Note If you are a registered student, you will need to log in to your learning management system to access and submit assignments.

Section 1.5 also includes a discussion on geological time. It is critically important for you to understand how much time is available, considering the excruciatingly slow pace of many geological processes, because without that understanding, you will have difficulties putting geological events into perspective. When we think of everyday events that are taking a long time to happen, we often say “it’s moving at glacial speed” because it’s well known that glaciers don’t move quickly. It’s true enough that they don’t, but glaciers, which advance at rates of metres to tens of metres per year, are positively speedy compared to most geological processes. Volcanoes, for example, grow at average rates of centimetres per year, less than one-hundredth as fast as glaciers, whereas sediments in lakes or the deep ocean accumulate at tenths of millimetres per year, about one-ten-thousandth as fast as glaciers move. Many geological processes are even slower than that.

Completing Exercises 1.3 and 1.4 will help you with your understanding of geological time, and the notation we use to express past geological times.

Also, work on the questions at the end of the chapter. The answers to these questions are available in Appendix 2 of your textbook. Click on the “Contents” tab at the top-left of any page, and scroll down to the very bottom.